Shenzheners Read online

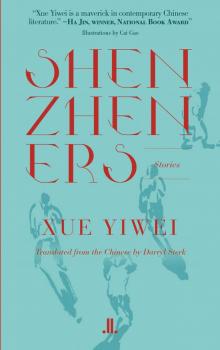

SHENZHENERS

stories

Xue Yiwei

Translated from the Chinese by Darryl Sterk

.ll.

Copyright 2016 © Xue Yiwei

Translation 2016 © Darryl Sterk

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced for any reason or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover design: Debbie Geltner

Cover image and interior illustrations: Cai Gao

Layout: WildElement.ca

Printed and bound in Canada.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Xue, Yiwei, 1964- [Chu zu che si ji. Selections. English]

Shenzheners / Xue Yiwei.

Short stories.

Partial translation of: Chu zu che si ji, 2013.

Translation: Darryl Sterk.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-988130-03-3 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-988130-04-0 (epub).--

ISBN 978-1-988130-05-7 (mobi).--ISBN 978-1-988130-06-4 (pdf)

1. Shenzhen Shi (China)--Fiction. I. Sterk, Darryl, translator

II. Title. III. Title: Chu zu che si ji. Selections. English.

PS8646.U4S4613 2016 C895.13’6 C2016-902309-5

C2016-902310-9

The translator wishes to acknowledge his wife, Joey Su.

The publisher is grateful for the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and of SODEC for its publishing program.

.ll.

Linda Leith Publishing Inc.

P.O. Box 322, Victoria Station,

Westmount Quebec H3Z 2V8 Canada

www.lindaleith.com

To the Irishman who inspires me.

Contents

The Country Girl

The Peddler

The Physics Teacher

The Dramatist

The Two Sisters

The Prodigy

The Mother

The Father

The Taxi Driver

The Country Girl

It was on the train from Toronto to Montreal that she discovered China’s youngest city. It was a charmingly sunny afternoon. She’d made it onto the train, breathless, a minute before it pulled out of the station. She needed to stand in the gangway for a bit to catch her breath. Then she walked into the forward carriage. She’d taken the train the weekend before, but this was the first time she’d seen it so full. She walked to the end and saw only a single empty seat, then hurried back, intent on claiming the seat with her shoulder bag before another passenger took it. That seat had been reserved for her by fate, she guessed. She sat down and unconsciously adjusted her blouse, slightly damp with sweat. Then she got out a packet of potato chips, a bottle of mineral water, and her copy of The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster. She ate the chips and read. At the same time, out of the corner of her eye, she checked out the occupant of the seat beside her. He was Asian, and he was resting his head on the window, as if daydreaming in the glorious sunshine. She’d made the trip by train from Montreal to Toronto every month for five years now, and this was the only time she’d ever walked through a carriage with only a single empty place, the only time she’d ever sat beside an Asian.

She lived in a village near Trois-Rivières, between Montreal and Quebec City. It was a ninety-minute drive from her house to Dorval Station, located on the outskirts of Montreal. It was to go see her mother, who was suffering from dementia, that she’d made the trip to Toronto. And she’d gotten on and off the train at that same station every time to avoid having to drive through the racket and the traffic of downtown Montreal. She thought of herself as a country girl and felt out of her element in the city.

Born in a little village in eastern Ontario, near the Quebec border, she’d grown up on a big farm. She was used to wide open spaces. She was used to the pace of life in the countryside. Even the country air, cow- and horse-dung laden, was to her a basic element of life. The university where she had studied was far from downtown. She’d double majored, in two language-related fields: French Literature and Translation Studies. To her, language was the most natural thing besides nature itself. She had loved language since childhood, and her passion had intensified her dependence on nature. “Every language is a capacious prospect,” she once wrote in her diary.

Soon after graduation, she married her elementary-school classmate, the boy who always used to tease her. They had grown up together on the farm, and their families had lived together for a time. Right before their first child was born, her husband, who was an architect, had found a job with a firm in Trois-Rivières. They left Ontario in what was for her an exciting move, because she’d always hoped French would become a part of her daily life; another capacious prospect, as it were. At her insistence, they settled in a village thirty kilometres away from Trois-Rivières. In front of their farmhouse were miles and miles of fields, and out back a seemingly endless forest. She hoped their children would have an idyllic childhood like hers. The way she saw it, a country childhood was a happy childhood.

She’d been a housewife in her sparsely furnished farmhouse for twelve whole years. The aerobics class she took in Trois-Rivières every weekend was her only social activity. Over the years, her husband had often suggested moving to the centre of Trois-Rivières or even to a suburb. He thought the city, with its superior recreational and educational facilities, was a better place to raise a child. She felt just the opposite, and every time he proposed moving she was adamantly opposed. Eight years before, on Christmas Eve, her husband announced that he had quit his job. He said he couldn’t take it anymore, he regretted ever coming to Quebec, he wanted to move back to Ontario, his only home. He’d rather live in any city in Ontario. Their daughter was not yet ten years old.

A chance opportunity allowed her to weather the marital storm, economically and emotionally, in just half a year. An aerobics classmate mentioned to her one day that the nuclear power station, which had just completed an extension, needed a French-English translator. The plant was less than fifteen kilometres from her farmhouse. No other potential workplace was closer, and French-English translation just happened to be her specialty. In the twelve years she’d spent as a housewife she’d sporadically taken similar translation jobs. She turned in her application and CV, got an interview, and got the job. The day she was given the contract she joked in her diary: “A marital crisis turns a housewife into a career woman.”

Soon she had two serious admirers, which was no surprise; she had a fashion model’s figure and movie star features. Maybe her legs and looks were due to hybrid vigour, for her mother was Austrian, born and bred in the Austrian Alps near the Swiss border, and her father was from the Scottish Highlands. Her fresh, youthful manner disguised her true age. Nobody would believe that she was the mother of two grown children and had spent twelve years as a housewife.

Between the two admirers, who were a contrast both in personality and in appearance, she chose the financial manager, who was half a head shorter than she was, because he also liked to read. She soon realized this wasn’t enough of a reason, because their reading interests didn’t overlap. He only liked Stephen King, while for her only Paul Auster counted as real reading. They had an on-again, off-again relationship for almost three years. The day they officially broke up, he gave her a copy of The New York Trilogy, the one she would bring with her wherever she went. It was a relationship without passion, so they parted without pain. She didn’t feel the need for it.

So she wasn’t on the rebound when, two days later, she happily accepted w

hen a brawny engineer asked her to go out on a date: a two-hour cross-country skiing outing in the woods behind the village. When the engineer took her home and asked whether he could kiss her, she neither agreed nor refused. And so they kissed a dusk-drenched kiss in front of the farmhouse, which delivered her into another relationship that was equally unrelated to her reading interests, and that failed to move her either aesthetically or physically. So, right before she went to Toronto that time to visit her mother, who was now mortally ill, she proposed ending it.

This time, breaking up had a subtle effect on her psychologically. She was tired of this kind of relationship—tired, it seemed, of relationships in general. She felt she’d need some time to recover from the funk she’d fallen into. Her mother’s dementia deepened her depression. She’d only made it onto the train at the last minute because she had wanted to spend more time with a mother who didn’t recognize her anymore. And now she was sitting beside an Asian man, the first time the Orient had come so close she could reach out and touch it.

Still less had she anticipated that this man would acknowledge her in the way he did. His eyes fluttered open, his head still resting on the glass. He was obviously taken aback, surprised that someone had taken the seat next to him. But then his expression changed, when he recognized the book she was holding. “You’re reading Paul Auster!” he said in a weak voice, clearly pleased.

She turned her head to smile at him. This was the scene she’d been imagining and waiting for, for many years: for a stranger in a strange place to notice the book she was reading. But she never expected the stranger to be an Asian. “You know about Paul Auster?” she asked, trying to keep her voice steady.

The Asian man hesitated, then said, “Not only do I know about him, but I also like his work a lot.” As he spoke, he leaned down and took a book out of his backpack, which he had placed under the seat, and handed it to her. “Look, this is the book you’re reading,” he said earnestly.

She found this incredible, because she didn’t recognize any of the words on the cover. She opened the book and saw the same unrecognizable text. Then she opened it to the same page she was reading and placed the two books side by side. “Are you sure they are the same?” she asked. There was wonder in her eyes and voice.

“I often ask myself the same question,” the man said. “Is a translation the same as the original work? Can a translation ever be faithful?”

His question seemed to challenge her. She was intrigued, but also disturbed. She also often challenged herself in translation, her chosen field of study, her profession. Could a translation faithfully represent an original? This was a constant dilemma. She didn’t feel like responding to the man’s query, even though she was sure the technical translation she did at the nuclear power station was faithful, perfectly accurate, and even though she agreed with Robert Frost about the untranslatability of poetry. She wasn’t so sure when it came to other kinds of translation.

He wasn’t waiting for her reply; it was a rhetorical question. “To think that Paul Auster would find a novel he himself wrote unreadable,” he said, pointing at his copy of The New York Trilogy.

She smiled and returned the book to him. “Is it well translated?”

“I often ask myself that same question,” he said. “Does a person who hasn’t read the original have the right to judge a translation? It was through translation that I came to like Auster’s novel, but was that the quality of Auster’s novel or the excellence of the translation?”

“Auster wouldn’t be able to answer these questions himself,” she said. “Even though he himself was a translator, from French to English.”

The Asian fellow said he knew. He also knew that Auster translated a modern history of China from French into English.

This was news to her. Again she felt both intrigued and disturbed. She felt as though the man sitting by her side was a true Auster aficionado, even though he had never read Auster’s original work. “Are you Chinese?” she asked, curious.

He nodded.

Then she asked whereabouts in China he was from.

“Have you been to China?” he asked.

She said she’d never been to China. Or anywhere else. She said she lived in the Quebec countryside, that she was just a country girl who had never seen the world.

“A country girl who is fond of Paul Auster!” the Chinese fellow said, weakly.

She blushed at the conspicuous hint of flattery in this comment.

“What places in China do you know?” he asked.

She said all she knew was Beijing and Shanghai.

“Oh, yeah.”

She then asked, a bit timidly, “Does Hong Kong count?”

He took a napkin and a ballpoint pen out of his jacket pocket. He drew a map of China on the napkin and marked Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong on it. Then he pointed with the point of the pen at a place close to Hong Kong and said, “That’s where I’m from. A very special city, the youngest city in China. A little fishing village twenty years ago, it’s now got a population of more than ten million.”

“I didn’t know there actually was such a young city in the world,” she said.

The Chinese fellow glanced over, obviously appreciative of her attention to his word choice. “Almost everyone in that city is an immigrant, just like here in Canada,” he said.

She liked the way he said “just like here in Canada,” giving her a perspective from which to imagine this youngest of cities. “So where were you born?” she asked, pointing at the napkin.

He tapped China’s northeast with the ballpoint pen. “That’s where I was born and where I grew up. In an old industrial city shrouded in smog.” He paused. “I never knew the taste of fresh air until I left.”

She blushed again. She felt as though he really cared about what she’d just said about being a country girl and all. He seemed to find it hard to believe.

They talked almost non-stop the whole trip, nearly five hours. She talked about her maternal and paternal grandparents, how they’d immigrated to Canada after the Second World War, and the different reasons why. And she talked about her parents. Her father had taken everything to extremes, while her mother did everything in moderation. They were quite incompatible, she said, but they loved each other their whole lives.

She talked of her two children, her lively, outgoing son and her quiet, introspective daughter. She said she didn’t know how the same mother could give birth to two kids who were poles apart. She even talked about her ex-husband. She said that even after all these years she still didn’t know the true reason for his sudden departure, that wanting to go home to Ontario and live in a city were excuses. She said she thought her ex might have homosexual inclinations. But she didn’t mention the two admirers who pursued her later on, as if wanting to leave the impression she had focused her thoughts exclusively on her two underage kids after her husband left.

The Chinese man said almost nothing about his current life. She vaguely sensed that he felt deeply afraid of the present. He only said that he was a “failed artist,” echoing the tone of voice that she had used for “country girl.” He said he had begun painting at six, that his mentor was the most famous artist in his hometown. This artist wasn’t only a mentor, but also a father figure. His study of painting was interrupted by the two jail sentences his mentor had to serve. The first time, his mentor was convicted of “hooliganism” for tracing Ingres’s The Bather. The other conviction came when someone found that the painting that had brought him fame represented “the western wind prevailing over the eastern wind,” which was the opposite of the Great Leader’s ideal. He was labelled a “counterrevolutionary,” like so many other victims of the Cultural Revolution. His mentor’s first marriage ended the first time he got out of prison. Saying she couldn’t possibly live with a hooligan, his wife took their two children and left. In fact, no girl in the city was willing to live with a h

ooligan. He ended up marrying a country girl a distant relative introduced him to.

“In China,” he explained, “a country girl is a girl without culture, taste, or an urban hukou—a residency permit that allows you to live in the city. That country girl left my mentor while he was serving his second prison sentence. She couldn’t live on her own in the city. She returned to her home village, deep in the mountains.”

He spent a long time talking about his mentor, while she wanted to hear more about his own experience. He said only the most general things about himself. When he left the smoggy city, he went to college in Beijing, majoring in oil painting. After graduation he went home and worked for a time, then immigrated to China’s youngest city, where he worked in a museum for thirteen years. And five years ago he made another move, this time to Montreal. “At first I didn’t know what the city meant to me. Now I know that this is where I belong.”

He made her feel sad when he talked of his sense of belonging in that weak voice of his. She also noticed how he turned his head to avoid the glare of the sun. She asked him why he had left China. He said he felt rootless, not just in the youngest city in China but also in Beijing and even in his home town. The feeling had intensified after his mentor died.

She found this explanation charming. “What’s it like to feel rootless in your native land?” she asked. “Didn’t you feel even more rootless when you got here?”

He gave her question some thought. “No, not more,” he said. “It’s just as much. I feel just as rootless here, a stranger in a strange land.”

“So it’s like the two countries you’ve lived in are a bit like these two books,” she said. “They’re the same book, just not the same.” She was a bit proud of her analogy, and noted his reaction of pleased surprise. Obviously he thought it was an analogy worth being proud of. This wasn’t the kind of analogy your typical country girl would make.

“Of course it’s quieter here. I like the quiet,” he said. “Not to mention the fresh air. In fact, the first fresh air I ever breathed in my life was here in Canada.”

Shenzheners

Shenzheners Dr. Bethune's Children

Dr. Bethune's Children